嗜睡

SOMNIA

| Ongoing |

功能性磁共振成像(fMRI)显示,当我们在回忆过去和想象未来时,我们的大脑活动保持惊人得一致的认知柔韧性。脑神经科学家推测这可能是一种能让我们更好应对未知事物的能力,我们对记忆的含糊与对未来的预测都呈现一种不可知的状态。

在摄影诞生以来,无数摄影师都以“记忆”为题去窥探摄影作为一种决定性的、时间切片的本质,但是大多数照片都被作为一种静态的记录,记忆在这个行为在这个过程中是被动的。实际上,我们的记忆会随着时间的流逝而改变,记忆常常会变得更加模糊,重新被诠释,重新一次又一次被涂抹上新的含义;就像个人记忆当中能窥见集体经验一样,照片的个人所属权也会随着集体时代的变迁慢慢淡化。

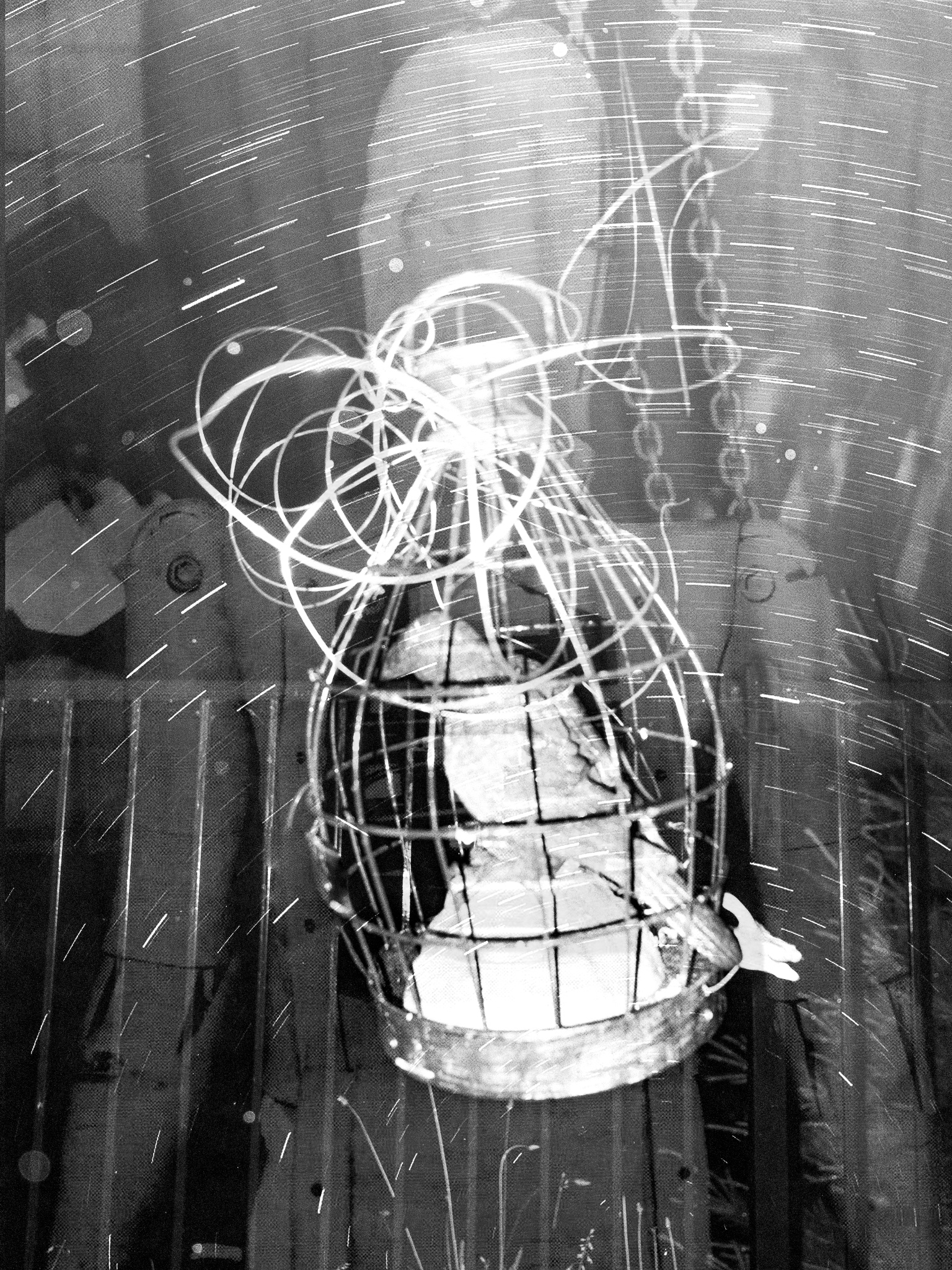

虽然照片相比起人类的记忆而言更加静止,但是它们并不深陷于时间的泥泞中。一张照片比起诞生于决定性瞬间,它更像诞生于按下快门之前脑内对将要发生一切的臆想。 我的作品《嗜睡》系列通过一系列的摄影术手法,从那些我们无需质疑的“纪实性真实到摆拍,档案照片,网络图像,包括后期的二次绘制,试着去捕捉照片/记忆在跨越空间、时间、和内容之间的某种潜在动力。

然而让一张照片的最终结果去模仿绘画一样要比模仿绘画的过程容易得多,如果我们将一张完整的画看作是一名画家的最终抉择的话,那么绘画的过程就是用笔刷作无数个 微小决定的过程。《嗜睡》的创作过程也是如此,正是创作过程中的不断微小决定建立起 的视觉骨架。我的美学观受中国明末画家八大山人朱耷影响很大,「他绘画的动物栩栩如生、灵动睿智,而且带有虚幻错觉。他笔下的鸟和鱼往往像是违反地心吸引力,在时空漂浮。」八大在画面中追求的简洁表意,不二法门,视觉上的幻象也是我在《嗜睡》中追求 的感官体验。

摄影终究还是一种对无尽的消亡的抗衡。可能正是因为人对最终消亡的恐惧,当今的图像才会以一个不可估量的指数性速度增长,创造出一个平行的图像现实。但是这些图像,他们中的大多数会像扔进湖里泛起微微涟漪的小石头一样,在流行文化的覆盖下缓缓 下垂。

所以当我们死后究竟谁拥有这些电子像素的所属权?虽然我们有生之年创造的图像会比我们活的更久,但是更有可能的是这些图像的拥有权会随着我们的死亡和我们一起步入坟土。或者说,如果记忆没法脱离一些证据(照片)被无条件信任的话,当我对我自己的照片作后期调试并且和他人的电子像素垃圾相结合的时候,对我那段记忆会有什么影响呢?如果我不断地调试同一张照片,增加一层又一层电子试剂,这又会怎么影响的记忆和那张照片相关事件的方式呢?这种手段能否作为一种艺术心理治疗来对待,或许可以将人的负面记忆变成正面的?

更进一步,通过《嗜睡》我想试着去质问是否可能利用摄影的媒介完全将我从记忆本身的累赘中释放出来?我观察到当我沉浸在对现实截取的拍摄体验中时,我自身就成了 一个空瓶,我不再去记忆现实中的细节和感受,取景框替代了我看到的现实,在拍摄中我不可能同时作为旁观者和参与者去和现实互动,最终的我获得的不是在某地的个人体验, 而是在某地的拍摄体验。那么这些被相机过滤过的记忆中,到底有多少我可以称之为我的?仿佛谁都不拥有照片,谁都不拥有记忆,一切都没什么意义。一切图像的反复调试,切割,分裂,结合,都是我靠着一种自我毁灭式的冲动来保持我记忆的流动性,而这一切的起点都源自于某个嗜睡的、世界末日光景一般的午后。

A scan of the human brain remains almost the same whether the subject thinks about the past or the future. Neuroscientists assume that this better equips us to deal with the unknown. The implication being that our memories of that which has already been are as uncertain as our expectations of that which is yet to come.

Owing to the way in which photographs appear to “capture” a slice of time, numerous photographers have addressed the theme of memory in their work - with varying degrees of insight. Yet most treat both photographs and memories as static phenomena; and the act of remembering as passive. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Indeed, our memories change over time; typically becoming hazier and less detailed; fusing with other unrelated reminiscences; and gaining culturally-prescribed significance. And just as private memories can become collective, images, too, can lose their individual ownership.

True, photographic memories are perhaps more static than those we carry in our minds, independent of technology. Yet they are by no means stagnant. Indeed, contrary to popular belief, photographs are not born of a “decisive moment.” Rather, they emerge from a process that extends chronologically both backwards and forwards from the moment of capture. It’s this dynamic evolution of image-memories across space, time, and context that forms the conceptual focus of Somnia; a body of work spanning the breadth of photographic techniques, from those we might uncritically describe as “documenting reality;” through staged scenarios; archival or found imagery; and interventions that are perhaps closer to painting.

However, to make a photograph superficially resemble a painting is much easier than replicating the process of its creation; where the final image is the result of countless micro-decisions in the form of brushstrokes. But it is just such a process that forms the backbone of Somnia. In particular I have been influenced by the works of Bada Shanren, a 17th Century Chinese artist-monk known for his disorienting use of juxtaposition, double meanings, and an eschewal of traditional perspective; techniques closely tied to Buddhist ideas of emptiness and worldly illusion.

Ultimately photography is an act of defiance against the irreversible anonymity towards which we all march. Perhaps as a consequence of this, today photographs are produced on an unprecedented scale, constituting a parallel - but no less real - world of images. Yet most of these will cause little more than a fleeting ripple on the surface of popular culture before sinking to the depths of obscurity.

Who owns our pixels after we die? It’s possible that some of the images we create in our lifetimes will outlive us. But in all likelihood our ownership rights over them will follow us to the grave. And yet, if memory cannot be trusted without the support of “documentary evidence” (i.e. photographs), what might be the effect on my personal memories if I combine my own photographs with this digital detritus? If I repeatedly manipulate the same image-memory, adding consecutive palimpsestic layers over time, how will this impact my recollection of the events depicted? Can this serve as a form of therapy, transforming negative memories into positive ones?

Going a step further, with Somnia I ask whether it is possible to use the photographic medium to free myself from the burden of memory altogether. And, consequently, also from the need to participate in unmediated reality. If I spend all day taking photographs, I become an empty vessel; not only has the camera done memory’s job, but it has also removed me from meaningful lived experience. That being the case, can I still legitimately claim these memories as my own?

SOMNIA

| Ongoing |

功能性磁共振成像(fMRI)显示,当我们在回忆过去和想象未来时,我们的大脑活动保持惊人得一致的认知柔韧性。脑神经科学家推测这可能是一种能让我们更好应对未知事物的能力,我们对记忆的含糊与对未来的预测都呈现一种不可知的状态。

在摄影诞生以来,无数摄影师都以“记忆”为题去窥探摄影作为一种决定性的、时间切片的本质,但是大多数照片都被作为一种静态的记录,记忆在这个行为在这个过程中是被动的。实际上,我们的记忆会随着时间的流逝而改变,记忆常常会变得更加模糊,重新被诠释,重新一次又一次被涂抹上新的含义;就像个人记忆当中能窥见集体经验一样,照片的个人所属权也会随着集体时代的变迁慢慢淡化。

虽然照片相比起人类的记忆而言更加静止,但是它们并不深陷于时间的泥泞中。一张照片比起诞生于决定性瞬间,它更像诞生于按下快门之前脑内对将要发生一切的臆想。 我的作品《嗜睡》系列通过一系列的摄影术手法,从那些我们无需质疑的“纪实性真实到摆拍,档案照片,网络图像,包括后期的二次绘制,试着去捕捉照片/记忆在跨越空间、时间、和内容之间的某种潜在动力。

然而让一张照片的最终结果去模仿绘画一样要比模仿绘画的过程容易得多,如果我们将一张完整的画看作是一名画家的最终抉择的话,那么绘画的过程就是用笔刷作无数个 微小决定的过程。《嗜睡》的创作过程也是如此,正是创作过程中的不断微小决定建立起 的视觉骨架。我的美学观受中国明末画家八大山人朱耷影响很大,「他绘画的动物栩栩如生、灵动睿智,而且带有虚幻错觉。他笔下的鸟和鱼往往像是违反地心吸引力,在时空漂浮。」八大在画面中追求的简洁表意,不二法门,视觉上的幻象也是我在《嗜睡》中追求 的感官体验。

摄影终究还是一种对无尽的消亡的抗衡。可能正是因为人对最终消亡的恐惧,当今的图像才会以一个不可估量的指数性速度增长,创造出一个平行的图像现实。但是这些图像,他们中的大多数会像扔进湖里泛起微微涟漪的小石头一样,在流行文化的覆盖下缓缓 下垂。

所以当我们死后究竟谁拥有这些电子像素的所属权?虽然我们有生之年创造的图像会比我们活的更久,但是更有可能的是这些图像的拥有权会随着我们的死亡和我们一起步入坟土。或者说,如果记忆没法脱离一些证据(照片)被无条件信任的话,当我对我自己的照片作后期调试并且和他人的电子像素垃圾相结合的时候,对我那段记忆会有什么影响呢?如果我不断地调试同一张照片,增加一层又一层电子试剂,这又会怎么影响的记忆和那张照片相关事件的方式呢?这种手段能否作为一种艺术心理治疗来对待,或许可以将人的负面记忆变成正面的?

更进一步,通过《嗜睡》我想试着去质问是否可能利用摄影的媒介完全将我从记忆本身的累赘中释放出来?我观察到当我沉浸在对现实截取的拍摄体验中时,我自身就成了 一个空瓶,我不再去记忆现实中的细节和感受,取景框替代了我看到的现实,在拍摄中我不可能同时作为旁观者和参与者去和现实互动,最终的我获得的不是在某地的个人体验, 而是在某地的拍摄体验。那么这些被相机过滤过的记忆中,到底有多少我可以称之为我的?仿佛谁都不拥有照片,谁都不拥有记忆,一切都没什么意义。一切图像的反复调试,切割,分裂,结合,都是我靠着一种自我毁灭式的冲动来保持我记忆的流动性,而这一切的起点都源自于某个嗜睡的、世界末日光景一般的午后。

A scan of the human brain remains almost the same whether the subject thinks about the past or the future. Neuroscientists assume that this better equips us to deal with the unknown. The implication being that our memories of that which has already been are as uncertain as our expectations of that which is yet to come.

Owing to the way in which photographs appear to “capture” a slice of time, numerous photographers have addressed the theme of memory in their work - with varying degrees of insight. Yet most treat both photographs and memories as static phenomena; and the act of remembering as passive. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Indeed, our memories change over time; typically becoming hazier and less detailed; fusing with other unrelated reminiscences; and gaining culturally-prescribed significance. And just as private memories can become collective, images, too, can lose their individual ownership.

True, photographic memories are perhaps more static than those we carry in our minds, independent of technology. Yet they are by no means stagnant. Indeed, contrary to popular belief, photographs are not born of a “decisive moment.” Rather, they emerge from a process that extends chronologically both backwards and forwards from the moment of capture. It’s this dynamic evolution of image-memories across space, time, and context that forms the conceptual focus of Somnia; a body of work spanning the breadth of photographic techniques, from those we might uncritically describe as “documenting reality;” through staged scenarios; archival or found imagery; and interventions that are perhaps closer to painting.

However, to make a photograph superficially resemble a painting is much easier than replicating the process of its creation; where the final image is the result of countless micro-decisions in the form of brushstrokes. But it is just such a process that forms the backbone of Somnia. In particular I have been influenced by the works of Bada Shanren, a 17th Century Chinese artist-monk known for his disorienting use of juxtaposition, double meanings, and an eschewal of traditional perspective; techniques closely tied to Buddhist ideas of emptiness and worldly illusion.

Ultimately photography is an act of defiance against the irreversible anonymity towards which we all march. Perhaps as a consequence of this, today photographs are produced on an unprecedented scale, constituting a parallel - but no less real - world of images. Yet most of these will cause little more than a fleeting ripple on the surface of popular culture before sinking to the depths of obscurity.

Who owns our pixels after we die? It’s possible that some of the images we create in our lifetimes will outlive us. But in all likelihood our ownership rights over them will follow us to the grave. And yet, if memory cannot be trusted without the support of “documentary evidence” (i.e. photographs), what might be the effect on my personal memories if I combine my own photographs with this digital detritus? If I repeatedly manipulate the same image-memory, adding consecutive palimpsestic layers over time, how will this impact my recollection of the events depicted? Can this serve as a form of therapy, transforming negative memories into positive ones?

Going a step further, with Somnia I ask whether it is possible to use the photographic medium to free myself from the burden of memory altogether. And, consequently, also from the need to participate in unmediated reality. If I spend all day taking photographs, I become an empty vessel; not only has the camera done memory’s job, but it has also removed me from meaningful lived experience. That being the case, can I still legitimately claim these memories as my own?

SOMNIA翻书视频

书名 《嗜睡》

摄影师 王文楷

书本设计 阿咸

出版 沼泽之地

视频 三影堂

音乐 4:36PM &5:59 PM- Celia Hollander

Photobook

Photographer Wenkai Wang

Book Design Shiro

Publish Swampland

Video Three Shadows Photography

Music. 4:36PM &5:59 PM- Celia Hollander